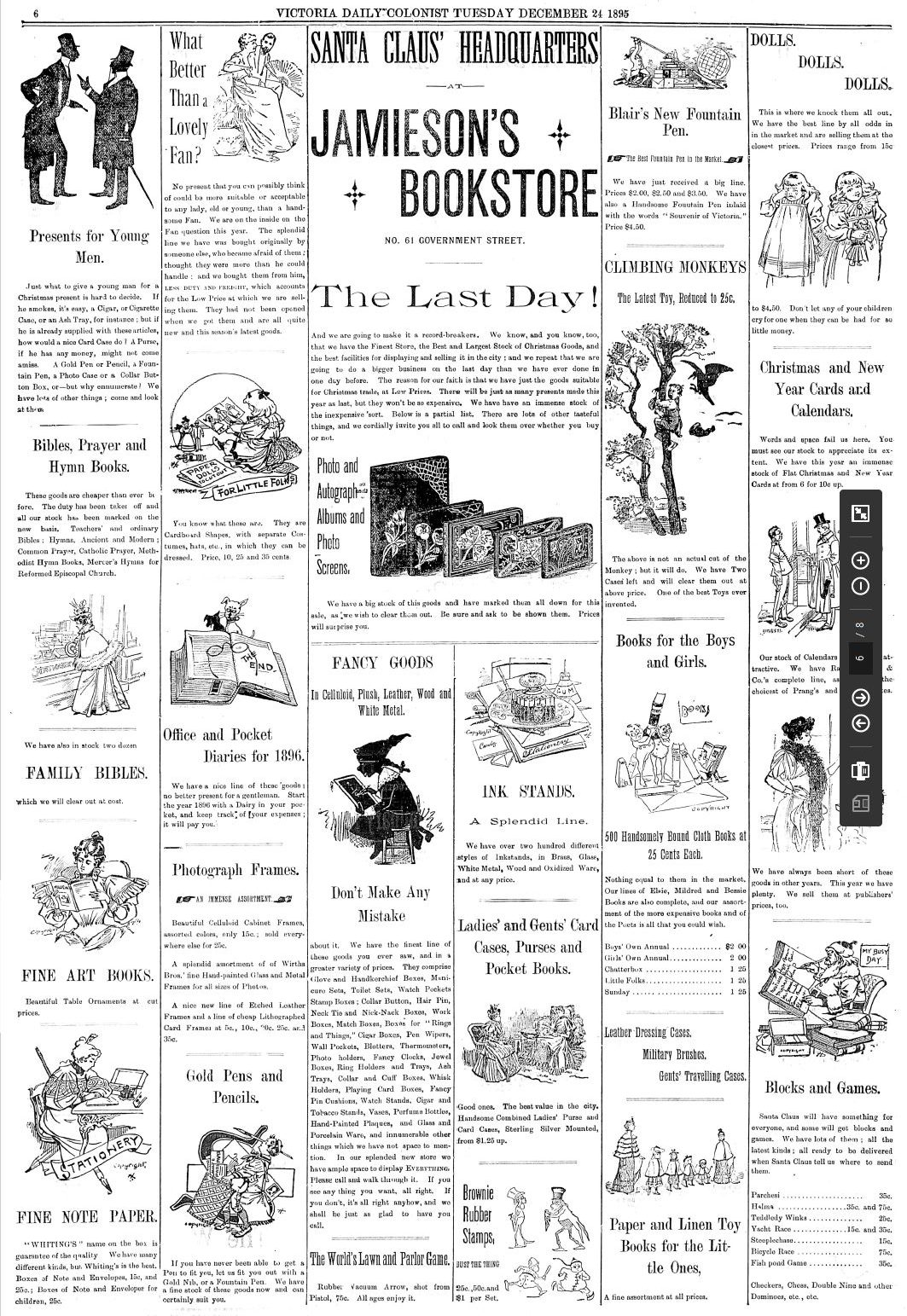

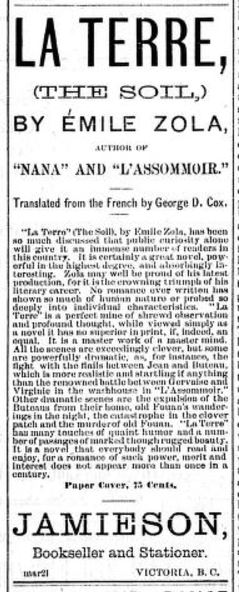

This splendid full-page ad is from Robert Jamieson’s bookstore in Victoria, 1895. (Click to enlarge.)

Tag: Robert Jamieson

At the Bookstore, 1888: Zola’s La Terre

One of the books for sale at BC bookstores in 1888 caused a great deal of hand-wringing and finger-wagging among members of the book trade—and, no doubt, a large number of discrete purchases by curious and more adventurous readers.

One of the books for sale at BC bookstores in 1888 caused a great deal of hand-wringing and finger-wagging among members of the book trade—and, no doubt, a large number of discrete purchases by curious and more adventurous readers.

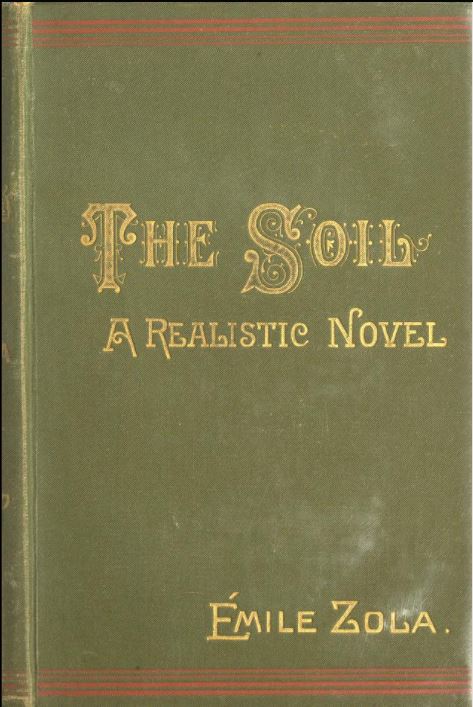

The book was Émile Zola’s The Soil, the English translation of his La Terre, first published in France by Charpentier in 1887.

The novel’s graphic violence and sexual content, although pretty tame by today’s standards (I’ve just finished it and was quite moved by it…more on that in a moment), caused quite a sensation on its initial publication in Europe.

The novel’s graphic violence and sexual content, although pretty tame by today’s standards, caused quite a sensation.

In anticipation of an English translation coming to the shores of British Columbia, the Daily Colonist asked in October 1887 if such a book indicated an undesirable change in literary tendencies.

“Zola’s work will, of course, be translated for perusal in this country…it will be read all the more eagerly as it is declared to contain matter which…is unfit for publication,” the newspaper predicted. “In [Victoria] book-sellers tell us that seventy-five per cent of the books read are novels, and novels of the sensational order; they expect a lively demand for ‘La Terre.’ The question arises whether our taste is drifting into the direction of impropriety.”

A book’s suitability to be read at girls’ boarding schools seemed to be the Daily Colonist‘s standard for respectable literature.

“In [Victoria] book-sellers tell us that seventy-five per cent of the books read are novels, and novels of the sensational order.” [Daily Colonist, October 15, 1887]

In 1888, the London publisher Vizetelly & Co. released the English translation of Zola’s novel as The Soil, and soon Canadian and American book industry publications came out against the book’s importation. “It would appear that ‘La Terre’ is even more nasty than Zola’s other novels, although that was needless,” sniffed Books and Notions in Toronto in December 1888.

Noting that Vizetelly had been fined $500 for publishing the translation and that the New York Post Office and US Customs authorities had refused it admission to the US, the Books and Notions article concluded, “We might ask does it ever pay a Bookseller to have this class of books on his shelves? They do sell, but do they attract or do they drive away the best class of trade?”

“We might ask does it ever pay a Bookseller to have this class of books on his shelves? They do sell, but do they attract or do they drive away the best class of trade?” [Books and Notions, December 1888]

In the following months, the publication provided an update that Vizetelly had been imprisoned for publishing Zola’s novel and that Canadian Customs officials had seized a shipment of Zola’s works bound for a Hamilton bookseller.

Meanwhile, at least one Victoria bookseller, Robert Jamieson, stocked the novel, and in fact highlighted its controversial nature in his promotions.

“Public curiosity alone will give it an immense number of readers in this country,” the Jamieson ad declared.

The ad went on to praise the novel and its author. “It is certainly a great novel, powerful in the highest degree, and absorbingly interesting. Zola may well be proud of his latest production, for it is the crowning triumph of his literary career.”

I have just finished the 1888 translation published by Vizetelly, and was gobsmacked. Where has Zola been hiding on me all this time?

It turns out that La Terre is the fifteenth novel in a twenty-book series set during the Second French Empire (1852-70). La Terre takes place in rural France, and its characters are mainly farming peasants whose lives feature endless drudgery just to get enough to eat and to clothe and shelter themselves.

“Whole years were necessary for the accomplishment of any really perceptible change in that weary, dull life of work and toil, which began afresh with every returning day,” one passage reads.

Most of the characters are completely miserable, and there are, indeed, several difficult scenes of physical and sexual violence, particularly against women and the aged. But there’s a raw realness to the story that drove me through page after page.

Perhaps it was the glimpse into these peasants’ impossible and violent lives that made the book so objectionable to the establishment of the day.

In 1894, Publisher’s Weekly reported that US Customs authorities in New York had decided to admit La Terre into the state at last, “though the book in question is one that must be handled with care, if it be not avoided altogether.”

***