***

History of Booksellers and Stationers in British Columbia

***

After Seth Tilley sold his Colonial Bookstore in New Westminster to Victoria’s Hibben & Carswell in 1863, they took on a local partner named George Cubitt Clarkson, who operated the store as Clarkson & Co.

Born in 1843 in Ontario (or Upper Canada, as it was then called), George was the eldest child and only living son of William and Jane Clarkson. William was quite a well-known pioneer in New Westminster, arriving in 1858, with his family following shortly thereafter.

William became the first president of New West’s municipal council in 1864 (he is sometimes called the city’s first mayor), and he remained politically involved throughout his life. He also ran the New Westminster House (a boarding house), acted as a real estate agent, owned an apple tree nursery, and amassed significant land holdings. Clarkson Street in New Westminster is named for the family.

George was twenty when he became a bookseller, and he reportedly did very well. He carried on the Columbia Street store much as Tilley had, advertising a large range of books, stationery, newspapers and periodicals, maps, musical instruments, toys and games, and other goods.

In March 1868, George added a circulating library to his store, and on June 10 that same year, the British Columbian applauded him for the “business energy and push” that had increased the circulation “of useful periodical literature throughout the mainland to double what it has been heretofore.”

The partnership between George Clarkson and T.N. Hibben & Co. was dissolved on June 20, 1868. At first George carried on Clarkson & Co. on his own, but by October, he had a new partner in his brother-in-law, John Stillwell Clute, who had married George’s sister Sarah in 1866.

Clute & Clarkson sold much more than books and stationery, operating more as a general store. Charles Major (another of George’s brothers-in-law, married to Mary Clarkson in 1867) joined the partnership too.

In 1870, George left business life when “the bent of his mind led him to adopt the church as his mission,” as his later obituary put it. He went to Ontario to attend Victoria College, where he prepared to enter the ministry. He also married during this time.

When George and his new wife returned to British Columbia, he served as a Wesleyan Methodist missionary in Chilliwack and Sumas. Now known as Reverend Clarkson, he remained in Chilliwack for two years.

Voting records for 1874 and 1875 list George as a “trader,” so presumably he left the ministry and returned to New Westminster. In 1877, he was appointed as a customs collector in Burrard Inlet. He would not hold the position for long.

On May 15, 1877, George died of paralysis (likely meaning a stroke) at the age of thirty-three. “His upright and kindly disposition had implanted…great respect and regard in a large circle of acquaintance, by whom his loss will be surely regretted,” his obituary in the British Columbian read. “For his bereaved family and young widow, we know that the strongest sympathy is everywhere felt. Mr. Clarkson leaves no children.”

***

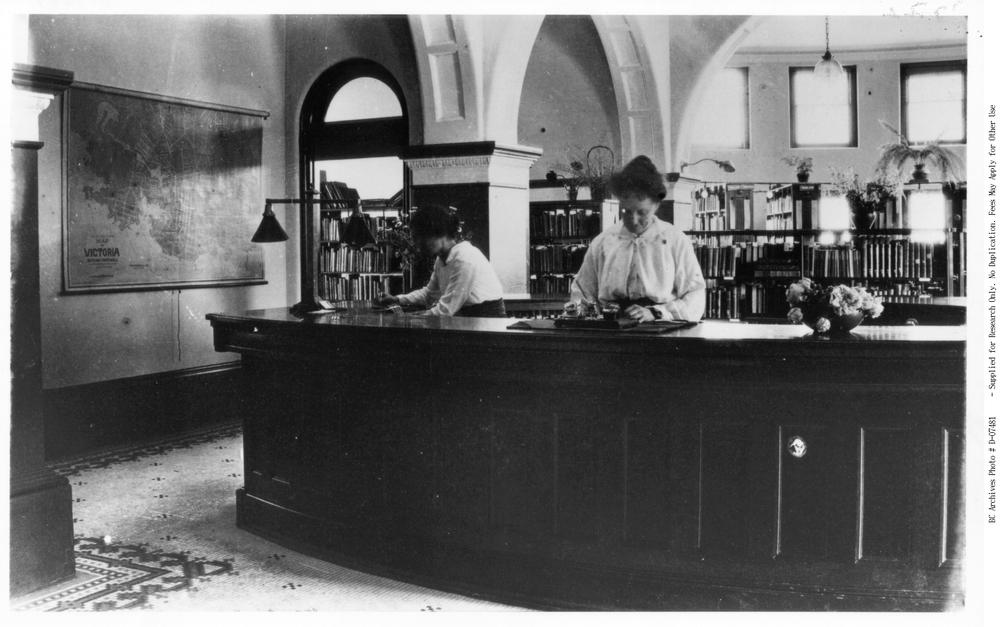

In the 1890s, T.N. Hibben & Co. was the place to meet in Victoria. “On a Saturday afternoon, or in the evenings, when the stores were open, you were sure to meet just about everyone you knew waiting for somebody else in Hibben’s store, poking among the books and passing the time of day with other people who were waiting for the people who were always late,” wrote James Nesbitt in his popular column “Old Homes and Families” in the Colonist (1).

“It was a friendly store, filled with books and the latest in stationery,” Nesbitt continued, then mentioned the constant presence of Thomas Napier Hibben (son and namesake of the founder), his brother, Parker, and William Bone, a partner in the business.

“And there was also Miss Mamie Stewart, whom everyone said knew more about books than anyone else in Victoria.”

“And there was also Miss Mamie Stewart, whom everyone said knew more about books than anyone else in Victoria.”

This grabbed my attention, as I hadn’t come across Mamie Stewart’s name before in connection with Hibben’s.

Nesbitt’s article said Stewart had eventually left Hibben’s for a job at the Victoria Public Library. “Everyone missed her, and said Hibben’s was never quite the same.”

Who was this Mamie Stewart? In my research of BC bookselling history, I so seldom come across the names of women (an unfortunate reality of the times) that I felt extra-motivated to find out.

Mamie Stewart, or Mary Elizabeth, her given name, was born in Victoria in 1870 to John and Margaret (McCoy) Stewart. John was a brass founder originally from Dundee, Scotland, while Margaret’s roots were in Ireland (2). Prior to arriving in Victoria in 1862, John spent five years in Lima, Peru (3). The family also included two sons, John Walter and Arthur Bernard, both younger than Mary.

As a girl, Stewart attended St. Ann’s Academy, an all-girls’ Catholic school in Victoria (4). “The school motto of St. Ann’s Academy was SIC ITUR AD ASTRA, which translates to ‘Such is the way to the stars’,” reads the history section of the school’s website. “Over and over again, the former students and teachers from the Academy spoke of the high expectations of the pupils there, and how this confidence in their abilities led them to achievements.”

The years she spent at St. Ann’s presumably instilled in Stewart her knowledge of and appreciation for literature.

In 1894, Stewart worked as a clerk at C.A. Lombard & Co. (5). The music store was located at 61 Government Street, just a few doors down from T.N. Hibben & Co., at 69-71 Government, presumably giving Stewart lots of opportunity to stop into the bookstore and get to know its proprietors.

By 1897, Stewart was employed as a clerk at Hibben’s (6). She remained with the company until at least 1905 (7), during which time she gained her reputation as knowing “more about books than anyone else in Victoria.”

As reported in the Nesbitt article, Stewart left Hibben’s for a position at Victoria Public Library, making the move sometime between 1905 and 1909 (8).

By this time, Mary’s father John had died of heart disease. Reporting his death, the Daily Colonist called him “a highly respected and well known resident of this city” (9).

At the library, Mary Stewart’s knowledge of books and way with people stood out, just as they did while she was at Hibben’s. In a 1914 report about the library’s rising circulation, the Daily Colonist gave Stewart much credit:

“The kindness and courtesy of Miss Mary Stewart, the manager of the circulation department of the library, makes the task of exchanging books a real pleasure to most people. There are many readers who must depend on the manager of this department for information and advice, and Miss Stewart is exceptionally well qualified to give both. To readers and book-lovers in Victoria she is an old friend, and she has added to her early training an earnest study of modern library methods. In Miss Stewart the head librarian has a very efficient and loyal co-worker, and the patrons of the library one of the kindest and most courteous, as well as most efficient, of public servants” (10).

“To readers and book-lovers in Victoria, [Mary Stewart] is an old friend.”

Mary Stewart is not to be confused with the other Stewart of Victoria’s early library history: Helen Gordon Stewart, who served as head librarian from 1912 to 1924.

Helen’s enormous contributions to the development of libraries and librarianship in BC are too numerous to mention here, but Mary made an impression on even this illustrious figure. In an interview Helen gave about her library career, she referred to Mary as “a fine a person as ever there was. I think she knew every person who came into [the library]” (11). Mary served as acting librarian a number of times when Helen was away.

Mary retired from the Victoria Public Library in 1936. After a lifetime of contributing to Victoria’s reading culture, she died at the age of seventy-four on November 11, 1944 (12).

Notes

(1) James Nesbitt, “Old Homes and Families,” Colonist (January 10, 1954): 1.

(2) 1901 Canadian census.

(3) “Pioneer Passes Away,” Daily Colonist (April 25, 1907): 6.

(4) “Lived Here 74 Years,” Daily Colonist (December 1, 1944).

(5) Williams Office British Columbia Directory, 1894.

(6) Henderson’s BC Gazetteer and Directory, 1897.

(7) Henderson’s BC Gazetteer and Directory, 1905.

(8) Directory of Vancouver Island and Adjacent Islands, 1909.

(9) “Pioneer Passes Away.”

(10) “Library Circulation,” Daily Colonist (February 7, 1914).

(11) “Interview with Dr. Helen Gordon Stewart,” in As We Remember It, edited by Marion Gilroy and Samuel Rothstein (Vancouver: University of British Columbia School of Librarianship, 1970), 21.

(12) “Lived Here 74 Years,” Daily Colonist (December 1, 1944).

***

***

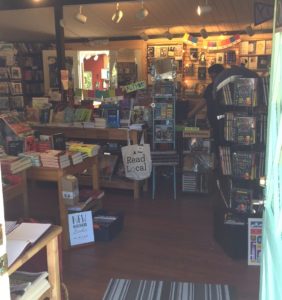

As I journey into BC’s bookselling past, I am still very much a bookstore lover of the present, and Galiano Island Books is a book lovers’ haven.

Whenever I visit Galiano, a visit to the store is a must, and I never leave empty-handed. (It’s impossible! So. Many. Wonderful. Books.)

Whenever I visit Galiano, a visit to the store is a must, and I never leave empty-handed. (It’s impossible! So. Many. Wonderful. Books.)

Owned by Lee Trentadue and Jim Schmidt, the cozy, welcoming store is celebrating its twentieth anniversary this year. In a recent conversation, Lee told me how she and Jim first fell in love with the idea of becoming booksellers and how they have kept the independent bookstore going strong for two decades.

Was there a bookstore on Galiano Island before you opened in 1997?

Lee: No, we started from scratch. There were some books sold at Montague Harbour, mainly for boaters, but there was no full-service bookstore.

Did you live on the island at the time?

Lee: We did. I was taking care of my grandkids in the city, so I lived three days a week in the city and then the rest of the week out here.

Were you coming from the book business?

Lee: No. I am a psychologist by trade and had worked at Vancouver General Hospital for many years, but I was looking for a bit of a change.

I read that your daughter was the one who initially wanted to open a bookstore…

Lee: That’s right. When Mary was exploring her career as a bookseller, she started inviting us to go along with her to book fairs and we kind of fell in love with the business. And then when she wanted to open her store, we said, “Why don’t you try opening on the island rather than competing with the Big Box stores and Amazon?” But she said, “I’m not quite ready to retire to an island.” And by that time we had found a property and decided we would go for it, so we bought the property and we both opened our bookstores within about four months of each other. Mary opened a store in North Vancouver, 32 Books. She ran it for close to ten years, but then decided to sell it.

What made you fall in love with the idea of running a bookstore?

Lee: I’ve always been a huge lover of independent bookstores, and all my life a reader, so I guess it’s just the magic of bookstores, the romance of the idea of opening a store—and I don’t think I’ve really ever lost that. I’m also a bit of a risk taker, I guess!

“I guess it’s just the magic of bookstores.” [Lee Trentadue]

Yeah, because in the late 1990s, the bookstore situation was—

Lee: Not good! The last twenty years have probably been the worst years in bookselling in a long time. But things are moving back to independent bookstores thriving again. We’ve weathered the storm, I think.

There seems to be a revival of people valuing printed books.

Lee: I think so. For different ages, it’s for different reasons. I know for young people, including my grandkids, they spend a lot of time on computers, and they find it stressful to read on e-readers and iPads. There are so many distractions on those devices, so they enjoy a book because that doesn’t happen. And there are people who have tried out e-readers and for whatever reason found them lacking or frustrating. And then there are those who never really left books.

There’s something about bookstores on islands. I have had the chance to visit a few recently, and I think they are better than in the city where I live, Vancouver. I imagine there must be some benefits to being on an island, but also some challenges.

Lee: People usually have time to browse when they’re on an island. And on islands, people do slow down. But yes, there were also huge challenges. We love to do events, and that was tricky getting authors to the island. So eight years ago we decided to have a literary festival. We started the Galiano Island Literary Festival, which happens each February and has been going strong.

Is the seasonal aspect of island tourism a challenge in terms of customers?

Lee: Not really. Increasingly, our tourist season has become longer and longer. For us, it now starts in February with the literary festival, then into March for the spring breaks, then April and May and we’re into the summer. It slows down in September, but there are still a lot of people travelling. September and October are still pretty busy, so there’s just a few weeks in there before Christmas starts. It keeps us steady. And, of course, our islanders are huge readers, which I did notice before I opened the bookstore!

Did you feel quite welcome when you opened?

Lee: Very much so, and that has continued.

And you launched the store with your husband, Jim [Schmidt]?

Lee: Yes, that’s right.

What did he do before becoming a bookseller?

Lee: He’s a neuropsychologist. He still works at that, at our private practice in Langley, but he loves to work here on the weekends. He comes and receives books, and he takes care of our online store. We sell some hard-to-get books, and our inventory is all online, and he takes care of that. He’s also very much a reader.

I imagine it must be a professional hazard for a reader to be surrounded by all those books!

Lee: At times it is overwhelming! There are books in every room in our house. And sometimes you think, ‘Okay, I’m not reading,’ and that lasts for a few hours. We have a complete library in the city and on the island, but both of us love that. Neither of us resents the mess of books. We’re always moving books around to make room for something else.

What’s your favourite part of running a bookstore?

Lee: I think the people. The customers. Here on the island, we’ve seen kids grow up who have been coming into the store all their lives.

Was your building there when you bought the property?

Lee: It was here, but we had to renovate it. It had been used for a few things over the years, like a real-estate office, a restaurant at one time, and then an art museum, and some sort of regional office. When we bought it, it needed to be gutted, so we did that. We got our floors from, I think it was a military base on Vancouver Island. They were walls, I think, that were repurposed for our flooring. Our cash desk was from an auction house, a liquidator. The guy doing all the interior renovations, he made all the bookshelves from scratch using wood from the island. They’ve withstood quite a few years!

When you first started, did you have any expectations about how long you would be doing this?

Lee: I was pretty serious. I don’t think you should go into bookselling thinking it’s going to be a short-term thing, especially if you love books, because I had a sense that it would be hard to leave. I said to someone when we opened, ‘Oh well, you’ll probably find me buried under a bookshelf one day.’ I’ve always had this image of little old people in bookstores who have been there for a hundred years. In bookstores I’ve been to all over the world, I always have that notion…of people who open a bookstore and just never leave.

“You’ll probably find me buried under a bookshelf one day.” [Lee Trentadue]

Are there any bookstores that stand out for you from those travels?

Lee: Shakespeare and Company in Paris; the Strand in New York City; City Lights in San Francisco; Powell’s, of course, in Oregon. For Canadian bookstores, Duthies, which I brought my kids to as babies. Steven Temple’s rare bookstore in Toronto; Pages in Toronto. I’m originally from Toronto, and there was also an art bookstore that Ed Mirvish, of Honest Ed’s, was associated with [it was David Mirvish Books, owned by Ed’s son]. I always visited it.

Do you have any bookselling mentors? People who helped you along the way?

Lee: I do. Cathy Jesson from Book Warehouse and Black Bond Books, and her brother, Michael Neill from Kelowna, are wonderful people for helping new booksellers. And Mel Bolen, of Bolen Books, of course, was just so welcoming to me. I remember sitting at a CBA [Canadian Booksellers Association] event, in Toronto, and she was holding my hand and saying “you’ll just do fine.” She was such a wonderful, welcoming, and talented bookseller. These were people, you could pick up the phone and they would answer any question you had.

In my research of nineteenth-century booksellers, I’ve found you can draw a web of these relationships between booksellers, where you might see clerks in one store who would then leave and open their own store. A continuous passing of the baton.

Lee: Yes, yes.

Do you have a sense of being part of a profession with such a long history?

Lee: Definitely, definitely. There’s a huge community of booksellers across Canada who we’re in touch with, and we help each other out a lot whenever something comes up. It’s a strong community of very good friends, and I think this has always been the case. And the history of bookselling is fascinating, going back hundreds and hundreds of years. It’s a very proud profession.

***

***

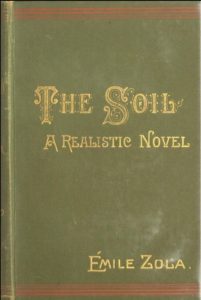

One of the books for sale at BC bookstores in 1888 caused a great deal of hand-wringing and finger-wagging among members of the book trade—and, no doubt, a large number of discrete purchases by curious and more adventurous readers.

One of the books for sale at BC bookstores in 1888 caused a great deal of hand-wringing and finger-wagging among members of the book trade—and, no doubt, a large number of discrete purchases by curious and more adventurous readers.

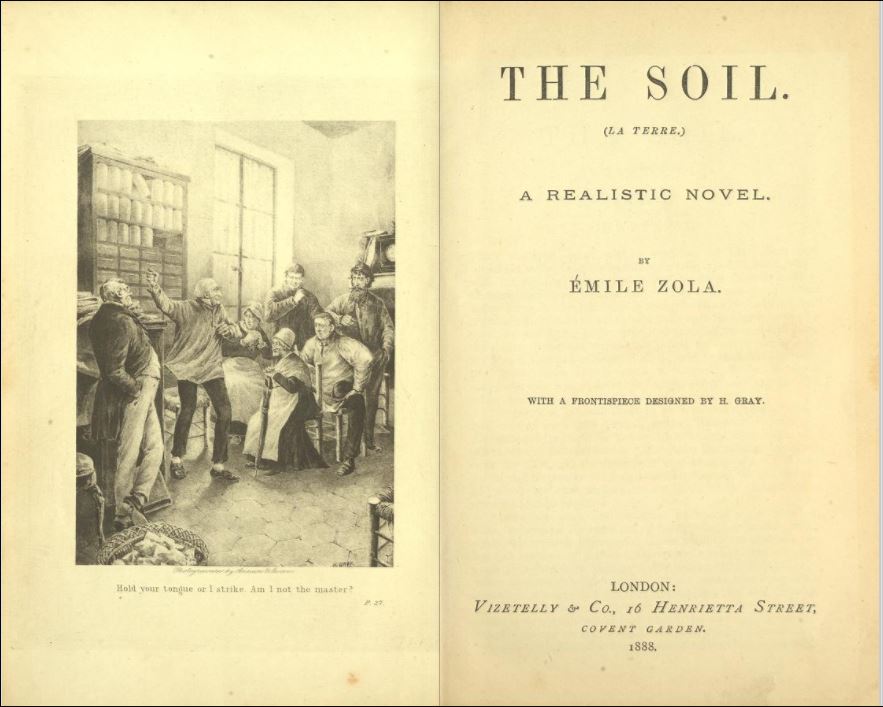

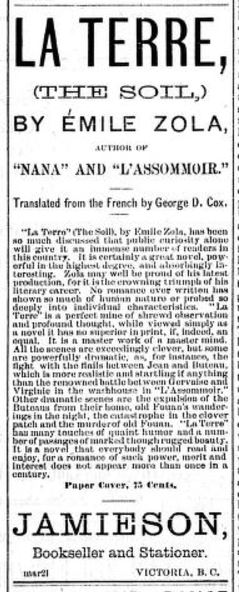

The book was Émile Zola’s The Soil, the English translation of his La Terre, first published in France by Charpentier in 1887.

The novel’s graphic violence and sexual content, although pretty tame by today’s standards (I’ve just finished it and was quite moved by it…more on that in a moment), caused quite a sensation on its initial publication in Europe.

The novel’s graphic violence and sexual content, although pretty tame by today’s standards, caused quite a sensation.

In anticipation of an English translation coming to the shores of British Columbia, the Daily Colonist asked in October 1887 if such a book indicated an undesirable change in literary tendencies.

“Zola’s work will, of course, be translated for perusal in this country…it will be read all the more eagerly as it is declared to contain matter which…is unfit for publication,” the newspaper predicted. “In [Victoria] book-sellers tell us that seventy-five per cent of the books read are novels, and novels of the sensational order; they expect a lively demand for ‘La Terre.’ The question arises whether our taste is drifting into the direction of impropriety.”

A book’s suitability to be read at girls’ boarding schools seemed to be the Daily Colonist‘s standard for respectable literature.

“In [Victoria] book-sellers tell us that seventy-five per cent of the books read are novels, and novels of the sensational order.” [Daily Colonist, October 15, 1887]

In 1888, the London publisher Vizetelly & Co. released the English translation of Zola’s novel as The Soil, and soon Canadian and American book industry publications came out against the book’s importation. “It would appear that ‘La Terre’ is even more nasty than Zola’s other novels, although that was needless,” sniffed Books and Notions in Toronto in December 1888.

Noting that Vizetelly had been fined $500 for publishing the translation and that the New York Post Office and US Customs authorities had refused it admission to the US, the Books and Notions article concluded, “We might ask does it ever pay a Bookseller to have this class of books on his shelves? They do sell, but do they attract or do they drive away the best class of trade?”

“We might ask does it ever pay a Bookseller to have this class of books on his shelves? They do sell, but do they attract or do they drive away the best class of trade?” [Books and Notions, December 1888]

In the following months, the publication provided an update that Vizetelly had been imprisoned for publishing Zola’s novel and that Canadian Customs officials had seized a shipment of Zola’s works bound for a Hamilton bookseller.

Meanwhile, at least one Victoria bookseller, Robert Jamieson, stocked the novel, and in fact highlighted its controversial nature in his promotions.

“Public curiosity alone will give it an immense number of readers in this country,” the Jamieson ad declared.

The ad went on to praise the novel and its author. “It is certainly a great novel, powerful in the highest degree, and absorbingly interesting. Zola may well be proud of his latest production, for it is the crowning triumph of his literary career.”

I have just finished the 1888 translation published by Vizetelly, and was gobsmacked. Where has Zola been hiding on me all this time?

It turns out that La Terre is the fifteenth novel in a twenty-book series set during the Second French Empire (1852-70). La Terre takes place in rural France, and its characters are mainly farming peasants whose lives feature endless drudgery just to get enough to eat and to clothe and shelter themselves.

“Whole years were necessary for the accomplishment of any really perceptible change in that weary, dull life of work and toil, which began afresh with every returning day,” one passage reads.

Most of the characters are completely miserable, and there are, indeed, several difficult scenes of physical and sexual violence, particularly against women and the aged. But there’s a raw realness to the story that drove me through page after page.

Perhaps it was the glimpse into these peasants’ impossible and violent lives that made the book so objectionable to the establishment of the day.

In 1894, Publisher’s Weekly reported that US Customs authorities in New York had decided to admit La Terre into the state at last, “though the book in question is one that must be handled with care, if it be not avoided altogether.”

***

***

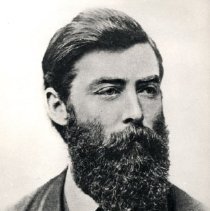

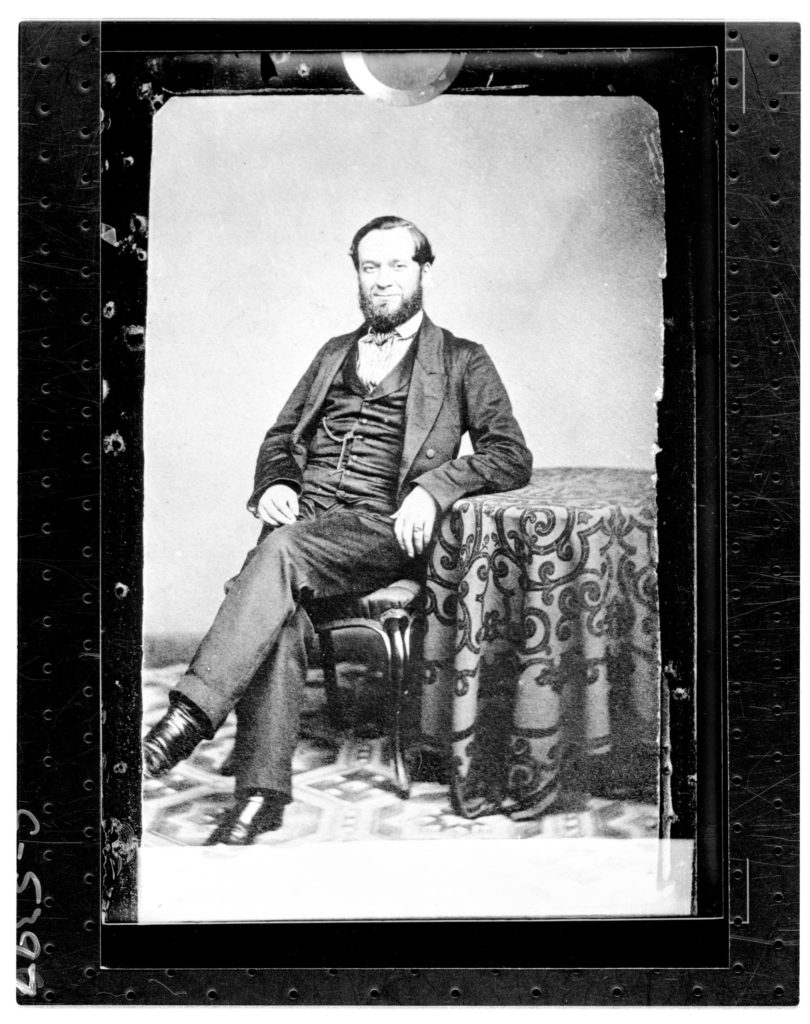

I just received this image of James Carswell, Thomas Hibben’s early bookselling partner in Victoria, from the Royal BC Museum and Archives. Newly digitized from a plate glass negative, it is the only one I have found so far of James. I felt a rush at finally seeing the face of someone from the distant past who I feel I’ve gotten to know, at least a bit, through my research of BC’s early booksellers.

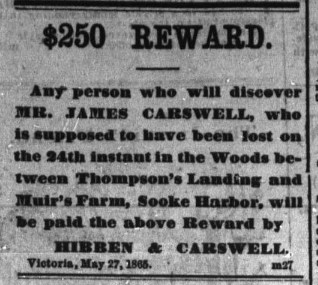

One of the stories that told me the most about James’s personality was an episode that started on May 27, 1865, when a notice appeared in the Daily British Colonist offering a reward for James, who had evidently gone missing on May 24.

He was still missing on May 29, when the newspaper covered the story of his disappearance in a long column.

“The search for this unfortunate gentleman is being prosecuted with the utmost vigor, several parties having left the city by both land and water for the spot,” the article read.

“The bush for some distance around the spot where Mr. Carswell was last seen was again pierced through and through yesterday by the party…but not the faintest clue could be found upon which to base any conjecture as to what had befallen the unhappy man. It is the opinion of men accustomed to the brush that Mr. Carswell could not have lost himself in the section of country where he is supposed to have strayed without some mark or trace being found to show where he had passed, and a faint hope is therefore not unreasonably entertained that he may still be alive.”

“A faint hope is…entertained that he may still be alive.”

By May 30, the reward had increased to $1,000, a huge sum at the time.

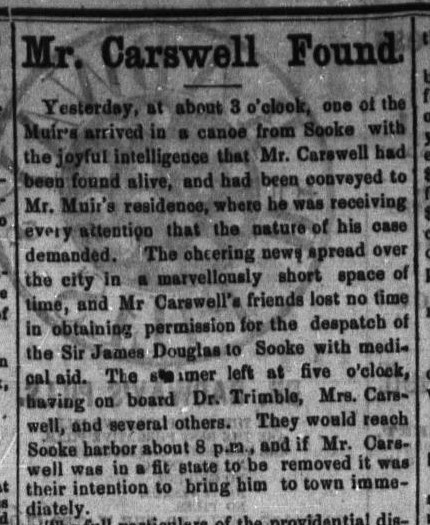

And then, hurrah, came the headline on May 31: “Mr. Carswell Found!” What’s more, he was reportedly in good condition and spirits.

And then, hurrah, came the headline on May 31: “Mr. Carswell Found!” What’s more, he was reportedly in good condition and spirits.

It seems James had taken a wrong turn on the Sooke trail he had been following after leaving a steamer at Robertson’s Landing. He had “endeavored to save time by making a short cut through the woods, but had not gone far before he found himself bewildered in the thick underbrush.”

When dusk fell, he managed to build a fire and make a bed out of fir boughs that he cut down with a pocket knife. The next day he tried again to find his way, but once again darkness forced him to set up a camp for the night. “His matches having given out, this night he suffered very much from cold.” He found plenty of water in the woods, but only a bit of chewing tobacco in his pocket kept his hunger at bay.

The next two days were more of the same. He periodically heard the shouts of the search party and tried to answer, only to become “completely baffled by the echoing of the reports through the forest.”

By now feeling “feeble and dispirited” and very hungry, he persevered for yet another day, but to no avail. “As evening approached his spirits sank, and he began to fear that his escape from this horrible position was hopeless. He accordingly with great presence of mind took a white pocket handkerchief and wrote on it some directions as to his affairs, and then raising his umbrella, which he always carried with him, he fixed it over his head so as to present a conspicuous mark, and lay down to what he must have thought was his last sleep.”

There he remained, dozing fitfully, for the next 36 hours. Waking up “considerably refreshed,” he tried yet again to make his way out of the thick forest. At last, this time he found the trail, and it wasn’t long after that when he came across some members of the search party.

In Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria, Edgar Fawcett recounted what happened next. When the searchers told James that they were glad to have found him, he replied, “‘Found me! Why, I am on my way home!'” When James learned that his partner Thomas Hibben had put up a reward for his discovery, “Mr. Carswell objected to pay,” wrote Fawcett, “protesting that [the search party] had not found him, but that he had found himself, and was on his way home when they met him. It caused a great deal of merriment, and was a standing joke for some time.”