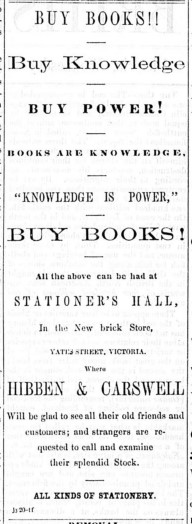

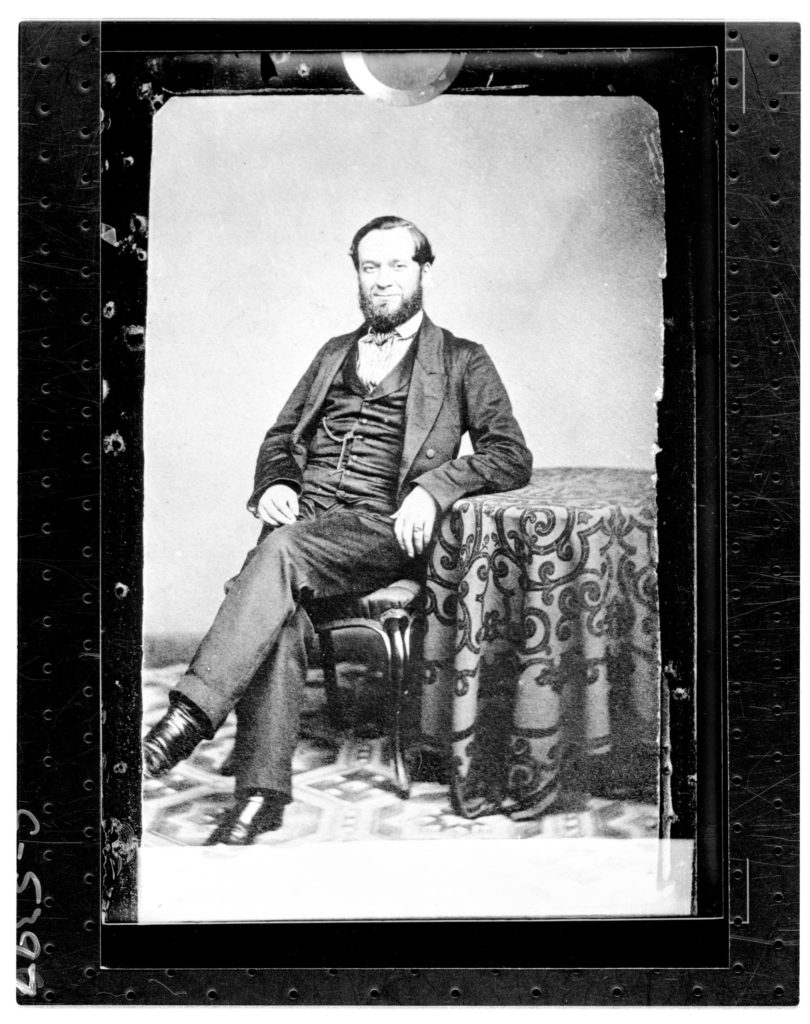

I just received this image of James Carswell, Thomas Hibben’s early bookselling partner in Victoria, from the Royal BC Museum and Archives. Newly digitized from a plate glass negative, it is the only one I have found so far of James. I felt a rush at finally seeing the face of someone from the distant past who I feel I’ve gotten to know, at least a bit, through my research of BC’s early booksellers.

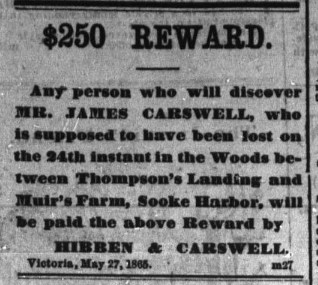

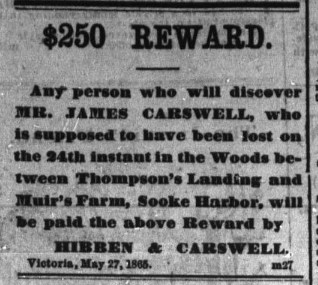

One of the stories that told me the most about James’s personality was an episode that started on May 27, 1865, when a notice appeared in the Daily British Colonist offering a reward for James, who had evidently gone missing on May 24.

He was still missing on May 29, when the newspaper covered the story of his disappearance in a long column.

“The search for this unfortunate gentleman is being prosecuted with the utmost vigor, several parties having left the city by both land and water for the spot,” the article read.

“The bush for some distance around the spot where Mr. Carswell was last seen was again pierced through and through yesterday by the party…but not the faintest clue could be found upon which to base any conjecture as to what had befallen the unhappy man. It is the opinion of men accustomed to the brush that Mr. Carswell could not have lost himself in the section of country where he is supposed to have strayed without some mark or trace being found to show where he had passed, and a faint hope is therefore not unreasonably entertained that he may still be alive.”

“A faint hope is…entertained that he may still be alive.”

By May 30, the reward had increased to $1,000, a huge sum at the time.

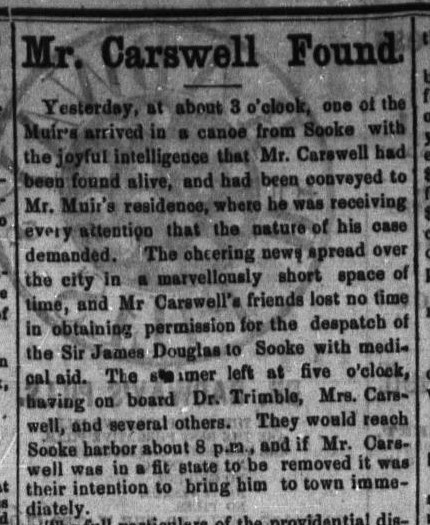

And then, hurrah, came the headline on May 31: “Mr. Carswell Found!” What’s more, he was reportedly in good condition and spirits.

And then, hurrah, came the headline on May 31: “Mr. Carswell Found!” What’s more, he was reportedly in good condition and spirits.

It seems James had taken a wrong turn on the Sooke trail he had been following after leaving a steamer at Robertson’s Landing. He had “endeavored to save time by making a short cut through the woods, but had not gone far before he found himself bewildered in the thick underbrush.”

When dusk fell, he managed to build a fire and make a bed out of fir boughs that he cut down with a pocket knife. The next day he tried again to find his way, but once again darkness forced him to set up a camp for the night. “His matches having given out, this night he suffered very much from cold.” He found plenty of water in the woods, but only a bit of chewing tobacco in his pocket kept his hunger at bay.

The next two days were more of the same. He periodically heard the shouts of the search party and tried to answer, only to become “completely baffled by the echoing of the reports through the forest.”

By now feeling “feeble and dispirited” and very hungry, he persevered for yet another day, but to no avail. “As evening approached his spirits sank, and he began to fear that his escape from this horrible position was hopeless. He accordingly with great presence of mind took a white pocket handkerchief and wrote on it some directions as to his affairs, and then raising his umbrella, which he always carried with him, he fixed it over his head so as to present a conspicuous mark, and lay down to what he must have thought was his last sleep.”

There he remained, dozing fitfully, for the next 36 hours. Waking up “considerably refreshed,” he tried yet again to make his way out of the thick forest. At last, this time he found the trail, and it wasn’t long after that when he came across some members of the search party.

In Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria, Edgar Fawcett recounted what happened next. When the searchers told James that they were glad to have found him, he replied, “‘Found me! Why, I am on my way home!'” When James learned that his partner Thomas Hibben had put up a reward for his discovery, “Mr. Carswell objected to pay,” wrote Fawcett, “protesting that [the search party] had not found him, but that he had found himself, and was on his way home when they met him. It caused a great deal of merriment, and was a standing joke for some time.”